AS THE SUN rose over the Sonora Desert in late June, Mark Zuckerberg stood beside a runway not far from the Mexican border.

Next to him stood Facebook vice president of engineering Jay Parikh and a few other colleagues, all eyes on the strip of asphalt that stretched toward the horizon. They had arrived a little before dawn, and they were the latecomers. A team of Facebook technicians began prepping the launch at midnight the day before. Among them was Martin Gomez, who sat inside a trailer at the other end of this Army airfield near Yuma, Arizona, taking the crew through its “go”-“no go” checklist. Then, a little past six o’clock, a truck taxied down the runway, pulling Aquila on a massive metal dolly stretched out behind it.

Aquila is the flying drone Zuckerberg and company are designing to provide Internet access in remote parts of the world. It’s made of carbon fiber, and it tops the wingspan of a 737. As the truck reached full speed, the drone’s on-board autopilot computer clipped the straps that held the aircraft to the dolly, and Aquila rose into the sky. Guiding itself via that same computer, the drone flew for a good 96 minutes in the restricted airspace of the Yuma Proving Ground before landing in the desert on its styrofoam skids—Aquila’s first successful flight.

Aquila is the flying drone Zuckerberg and company are designing to provide Internet access in remote parts of the world. It’s made of carbon fiber, and it tops the wingspan of a 737. As the truck reached full speed, the drone’s on-board autopilot computer clipped the straps that held the aircraft to the dolly, and Aquila rose into the sky. Guiding itself via that same computer, the drone flew for a good 96 minutes in the restricted airspace of the Yuma Proving Ground before landing in the desert on its styrofoam skids—Aquila’s first successful flight.

The team had planned for the drone to spend half an hour navigating the winds and other turbulence, says Gomez, Facebook’s director of aeronautical platforms. But things were going well enough that they extended the flight, gathering still more data on the drone’s four motors, its autopilot system, its batteries, and its radios

Gomez and his team have flown several significantly smaller prototypes over the past year—a total of twenty-three flights in Great Britain and the US—but on June 28, they finally launched the real thing, all 140 feet of it, as Facebook revealed today. The flight didn’t break any records. It didn’t reach the heights where Facebook says the drone will eventually soar. And Aquilla is still unfinished, lacking the solar panels, high-altitude batteries, Internet antennas, and other equipment she will eventually carry into the skies. But her maiden voyage is a milestone for Facebook—and the larger effort to push the Internet into all those places that don’t already have it.

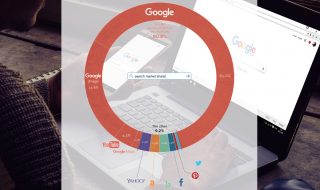

As Google works to expand the Internet with its own flying drones and high-altitude balloons, Facebook is fashioning all sorts of contraptions to spread online access far and wide, including new wireless antennas, lasers, and satellites. In the process, both companies are furthering their own ends. If they expand the Internet’s reach, they expand the reach of Google and Facebook. But they’re also helping the world communicate, which is why this short flight over the Arizona desert is so important. By Facebook’s estimates, about 1.6 billion people live in areas that don’t offer mobile broadband.

Yes, others have flown drones for far longer, says Phil Finnegan, an analyst with the Virginia-based Teal Group who specializes in unmanned aerial vehicles. But that’s not exactly the point, he says, because Facebook isn’t in competition with other drone makers. The social networking giant doesn’t plan on operating its own flying Internet drones—just as it doesn’t plan on selling its own wireless antennas. It wants to give others a means of more easily expanding the reach of the Internet.

Facebook aims to give away the blueprints for its drones and other Internet devices, so that anyone from local governments to Internet service providers can construct a new way to get Internet signals into hard-to-reach places. Aquila is designed to fly in the stratosphere, climbing above the weather as it delivers signals to rural areas down here on Earth. In some cases, this is cheaper and easier than running landlines across the surface. Once airborne, these drones could beam Internet service to a terrestrial base station, which could then send the signal on to phones and PCs. Or squadrons of Aquilas could broadcast straight to phones without a waystation in the middle.

The plan is to power these drones with the sun, so they can stay aloft for months at a time. Aquila isn’t yet ready for that, but Facebook says the current design can operate on the power of about three hair dryers at altitude—and about a single hairdryer at sea level. “We want this plane to fly as slowly as possible,” Parikh says. “It is very big and has a lot of lift, but it doesn’t need a lot of power to move it forward.”

Currently, the drone runs on lithium ion batteries a lot like the one in your cell phone, and during its maiden flight, it reached an altitude of about 2,000 feet. But Facebook plans eventually to install solar panels that plug into some other as-yet-unspecified battery technology suitable to flights that climb much higher—about 60,000 to 90,000 feet—where temperatures are significantly lower.

When flying to such heights, the drone won’t launch with the help of truck and dolly. Parihk says it may ride to 60,000 feet on a balloon, but the team has yet work out the details. And there are so many other problems that still need solving. They must install and test Aquila with its communications payload—the gear that will beam that Internet signal down to earth. They must reduce the cost of this flying drone. And, well, they need good ways of bringing thing down. On its maiden voyage, Aquila suffered some “structural failure” just before landing. At the moment, Facebook’s drone is still years from completion. But at least it’s off the ground.

So