Snow rests on the eagle statue atop the U.S. Federal Reserve in Washington January 26, 2016. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst

The Federal Reserve will be patient as it decides how trouble overseas could hit the U.S. economy, a Fed policymaker said in an interview, suggesting the central bank will be slower to raise interest rates this year.

Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan said on Friday it was “significant” that the Fed decided this week to no longer describe the risks to the U.S. economy as being “balanced,” a term that meant officials were comfortable with their view of the outlook.

“It should be saying to people (that) we are going to take some time here to understand what is going on,” Kaplan told Reuters in the first public comments by a top policymaker since the central bank’s decision on Wednesday to hold rates steady.

The Fed raised rates for the first time in a decade in December, at which time policymakers signaled four further hikes would come in 2016. But since then economic weakness in China, Europe and Japan have prompted deep skepticism among investors, who now see only one hike this year.

Kaplan’s comments seem to support that cautious view.

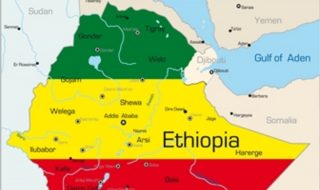

Global equities and oil prices plunged through most of January and Kaplan said he expected overseas challenges to affect the U.S. economy. He characterized as “clumsy” China’s policy moves over the last six weeks to counter turmoil in Chinese financial markets.

“When you put all that together I think there is good reason to be patient (and) take more time to assess the impact on the U.S. economy,” said Kaplan, who does not have a formal vote on Fed policy this year but who takes part in all deliberations.

Kaplan declined to say how quickly he expects the Fed to lift interest rates this year.

But he said a tightening of global financial conditions, including relatively steeper lending rates for investment grade companies, was getting his attention.

The Fed’s next policy meeting is in March, when policymakers will also release new forecasts on how steep the path of interest rates will be this year.

“It’s not going to be any steeper,” said Kaplan, who took the reins at the Dallas Fed in September.

While the Fed has embarked on what it hopes will be a gradual tightening path, other major central banks are headed in the opposite direction with stimulus that has boosted the dollar’s value and helped keep U.S. inflation well below the Fed’s 2 percent target.

The Bank of Japan on Friday made the shock decision to cut rates below zero, prompting some to warn of “currency wars” that do little for global growth.

Kaplan, who in the 1990s ran Goldman Sachs’ Asian banking operations out of Tokyo, said the move “will have some effect clearly on the dollar and we are very mindful of that,” adding that Japan is “doing what it needs to do.”

He said Chinese officials are still learning how to manage their whip-sawing financial markets. The country used so-called “circuit breakers” to halt trading when its stock markets were plunging this month, but scrapped the tool after it appeared to exacerbate the selloff.

“It’s unusual for them in my experience to appear as clumsy as they were over the last six weeks and that clumsiness has jarred people,” Kaplan said, adding that China was unlikely to “melt down” in part because of its substantial dollar reserves.

Wall Street’s biggest banks still see three Fed rate hikes this year, though many others now see the Fed getting overtaken by a global economic downturn.

The Fed’s statement “signaled that it is now hostage to international developments and markets,” said Mohamed El-Erian, the chief economic advisor at Allianz, who expects two hikes this year and possibly none at all if economic and financial market conditions worsen.

Source:Reuters/Jonathan Spicer/Jason Lange