Japan's economy has been struggling for two decades and faces some of the same problems the U.S. has. Here, a man in Tokyo passes an electronic board displaying falling global markets.

Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda sprung another surprise on investors Friday, adopting a negative interest-rate strategy to spur banks to lend in the face of a weakening economy.

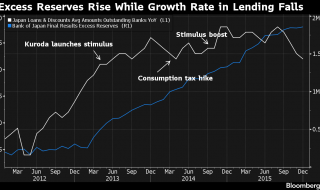

The move to penalize a portion of banks’ reserves complements the BOJ’s record asset-purchase program, including 80 trillion yen ($666 billion) a year in government-bond purchases, which was kept unchanged at the board meeting. By a 5-4 vote, Kuroda led his colleagues to introduce a rate of minus 0.1 percent on certain excess holdings of cash.

Long a pioneer in adopting unorthodox policies to tackle deflation and revive economic growth, the BOJ is now taking a page out of European policy makers’ playbooks in the goal of stoking inflation. The yen tumbled after the announcement, which came after Kuroda just last week rejected the idea of negative rates.

“This clearly shows the BOJ wanted to weaken the yen and raise the price of import goods and boost inflation,” said Daisuke Karakama, an economist at Mizuho Bank in Tokyo. “We don’t know this negative rate policy will be good for the economy in the end,” he said, adding that success in Europe doesn’t guarantee the same for Japan.

Market Impact

The yen dropped, though not as much as it did immediately after Kuroda began his campaign in April 2013 and in October the following year when he added to stimulus. It traded at 120.94 against the dollar at 6:49 p.m. in Tokyo.

Stocks zigzagged, rallying for 28 minutes, then falling sharply only to rise again as traders digested the news. The benchmark Topix index closed 2.9 percent higher.

While some analysts suggest that Kuroda, 71, is running out of options to spur inflation and growth in Japan, he said Friday that the addition of a negative rate gives him another policy tool.

The BOJ won’t hesitate to add further monetary stimulus if needed and has scope to make deeper cuts to the negative rate or to increase its asset purchases, he said.

The BOJ made its announcement hours after government reports showed the Japanese economy was unexpectedly weak in December, with bigger-than-anticipated declines in industrial production and household spending. With exports contracting and concerns resounding about the slowdown in China, the external environment has turned sour for the world’s No. 3 economy.

While Kuroda said last week in an interview that there were no signs yet that this month’s financial-market turmoil had damaged corporate plans in Japan, he said they bore watching. Friday’s move signals he concluded there was a need to act, and he swung four of the nine board members behind him — his two deputies, a former Toyota Motor Corp. executive and an academic economist who last year suggested negative rates as a potential strategy.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration will have the opportunity to nominate a new board member to replace Sayuri Shirai, who voted against the change in interest-rate policy. Her term finishes in a few months. Koji Ishida, who also opposed the move, is due to step down midyear.

Starts February

The negative rate will be imposed on reserves worth about 10 trillion to 30 trillion yen initially and will apply only to new reserves that financial institutions deposit at the central bank, according to people familiar with knowledge of the matter. The change will take effect on Feb. 16 and is similar to programs at some central banks in Europe, the BOJ said.

With the bulk of banks’ reserves continuing with a positive 0.1 percent rate, this could help to contain any negative spillover effects such as damage to their earnings that would undermine lending and growth.

Also, the central bank delayed the timing of reaching the 2 percent price target to around the six months starting in April 2017, the third postponement in less than a year. The bank now sees inflation rising 0.8 percent in the 12 months starting this April, down from a previous forecast of 1.4 percent.

Kuroda’s task in achieving his goal of sustainable inflation remains difficult amid subdued wage growth and a renewed decline in oil prices, which had led a growing number of economists to predict additional stimulus later this year. His resolve to do “whatever it takes” to meet the price target — a phrase he has repeated in speeches in recent months — will be tested if inflation and growth prospects worsen further.

Abe’s Support

Before the meeting Abe didn’t indicate his desire for the bank to move now; he reiterated this week that the government would work with the BOJ to end deflation. Etsuro Honda, one of his economic advisers, said Thursday that the BOJ should bolster stimulus at this meeting because of waning inflation expectations.

The BOJ’s challenge has much in common with that of counterparts in developed nations where inflation rates have run below policy makers’ targets, in part because of the slump in oil prices. European Central Bank President Mario Draghi last week signaled more stimulus will come in March from that bank as the inflation mandate is crucial.

The BOJ board will hold its next policy meeting on March 14-15.